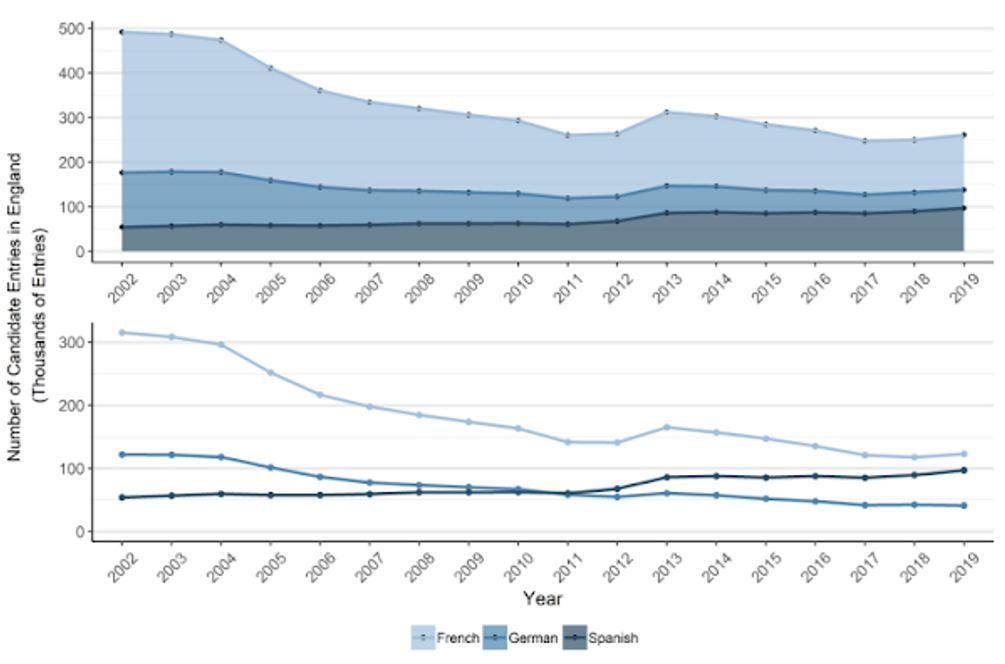

Britain’s Modern Foreign Language (MFL) study is on its knees, and has been buckling for some time. A report by Ofqual, the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation, highlighted that the number of exam entries for the top three MFL subjects (French, Spanish, and German) had split by nearly half between 2002 and 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of entries for French, German and Spanish GCSE exams between 2002 and 2019 in England. The top graph shows combined entries to French, German and Spanish in each year, while the bottom graph shows entries for individual subjects. (Source)

This drop is also reflected by ‘other modern languages’ having the largest reduction in enrollment rates of all English Baccalaureate subjects in the past few years. Unsurprisingly, these trends narrow the pool of MFL students at A Level and higher education. What we are left with is around 95% of the British population – with English as a first language – being monolingual, whilst most of our European counterparts have multiple languages firmly under their belt.

There are a myriad of reasons behind Britain's linguistic collapse. However, at the core of its demise is the poor perception of foreign languages in Britain and their subsequent neglect in education policy. The pervasive notion of a ‘global English’ spoken by all ostensibly leaves no point in learning other languages, since ‘everyone else speaks English anyway’. In fact, this can be easily debunked, as 70% of the world’s population do not speak English. Moreover, the concept of global English seems nothing more than wool being pulled over the UK’s eyes when seeing our monolingualism for what it truly is: not a default of English dominance on the global stage, but a humiliating reflection of the state of our education system.

UK state schools suffer from chronic underfunding, forcing teachers to abandon subjects when student uptake is not high enough. Regrettably, language learning has been at the top of this scrap pile. Students’ abandonment of MFL is subsequently a product of the ‘global English’ rhetoric, paired with lower-quality teaching brought by monetary constraints. Equally, inconsistency between schools on language syllabuses, and frequent reports on the subject’s perceived difficulty have driven students away from MFL study, instead favouring other ‘easier’ subjects.

It is hard to believe that EU children, where MFL is taken by 96.8% of secondary school students, are innately hard-wired to learn languages better than children in the UK. Therefore, Britain’s monolingualism at school level must be an external problem. Cultural mythology, financing and teacher-training deficits, as well as a potentially over-successful policy by David Cameron to advance STEM teaching at the expense of humanities, arts and languages in the late 2010s, are more to blame for the current situation.

The Higher Education Policy Institute, an independent think tank, correctly identified the true trigger point of MFL’s decline – New Labour’s decision to stop foreign languages being a compulsory GCSE option. This decision typically appears as a minor, unelaborated bullet point buried within Labour’s otherwise immaculate and well-received education plan.

The predominant reason for making languages optional after the age of 14 was to permit students “who were wholly unsuited, unmotivated or unable to learn a language to make better use of their time.” This, coupled with a novel initiative to make language teaching compulsory in primary schools, intended to make students organically pursue language study, while also giving a few others room to do something else. The central flaw to this operation was its overdependence on future funding to improve language teaching from a younger age, since this ultimately never came. In reality, primary teachers were not provided with the staff, training or resources to teach languages to a proper standard, making any preliminary learning effectively pointless. The government’s belief that teenagers would do something renowned for being difficult by choice, with no apparent benefits, was equally a bad show of judgment.

What makes Labour’s decision more baffling was how they were shown evidence of such a policy’s failure by past records, but still opted to go through with it. During a preceding parliamentary debate, the conservative opposition referred to the 1991 decision to make languages compulsory, which saw MFL uptake go from 30% to almost all pupils. Undoing this policy with little to no explanation has caused serious ramifications for an entire generation, as the 2004 policy marks a sharp decline in language uptake.

Since then, governments have fired policy after policy to try and compensate for the drop: the introduction of the English Baccalaureate, a 2011 GCSE qualification that incorporates languages into its list of required subjects; some extra language funding; and most recently, a reduction to the syllabus so students feel less intimidated by course content. Sadly, these are all band-aid solutions to a deeper-cutting issue. A 20-year dearth in new language students has already instigated the self-fulfilling prophecy of there being fewer home-grown language teachers, meaning fewer children will ever be able to learn languages at school. In other words, language study will only continue to fall.

Bringing back compulsory languages at GCSE-level is not the only required change, but it would be the best start. If the aim is to reestablish MFL’s importance and train young people to be bilingual, merely simplifying the content is a disservice to students trying to develop their linguistic competencies. Compulsory language teaching would need to be backed up with further funding to support effective language learning methods, such as hiring native speakers, funding intercultural trips, as well as standardising teacher training, so all UK students would receive the same tutelage.

The UK, and the government, need to change attitudes to MFL before it is too late. In the face of Brexit, the country’s position on the global stage is already weakened. The loss of soft power acquired through its former position in the EU, as well as new restricted freedoms to integrate with other countries, means young Brits need language skills to compete with their international counterparts when job-searching or working in a global business setting. More important, however, is the cultural aspect. In a globalised world, it is critical to understand others’ perspectives to promote harmony and understanding. This is why it is no good to think your language is the only one that matters.